by Sara Georgini, Series Editor, The Papers of John Adams

The Papers of John Adams, Volume 20, spans a formative era in the development of our federal government, stretching from June 1789 to February 1791. We used 301 documents to tell the legislative story of the first federal Congress, foregrounding John Adams’s creation of the office of the vice presidency amid the nation’s struggle to implement the new U.S. Constitution. With outliers North Carolina and Rhode Island repeatedly delaying ratification of the Constitution, Congress battled through three busy sessions of debates. Meeting for the first time in New York City’s half-built Federal Hall, congressmen tussled over how to collect revenue and where to locate the national capital. They spent weeks filling posts, and setting up the key departments of state, treasury, and war. John Adams’ ever-candid comments reveal firsthand the challenges of that inaugural Congress.

Equally perplexing—and challenging—to John Adams was the scope of his new federal role. The U.S. Constitution said little about what a vice president’s powers were, and so Adams was largely left alone to interpret the charge. Here’s what we learn in his letters: From his earliest days in office, Adams etched out clear boundaries for the vice president’s powers. He forwarded a flood of patronage requests to George Washington. Adams focused his energy on presiding over the Senate, where he broke several major ties amid rising partisan conflict. Overall, Adams found his Senate duties “Somewhat severe—sitting just in the same place, so many hours of every day.” Though he could be petulant about the daily grind of politics, Adams was optimistic about the “National Spirit” of his colleagues, who were constructing the tripartite federal government that he had long envisioned. Whether or not the union would hold, as regional interests repeatedly impeded congressional action, remained Adams’ chief concern. As he told one friend, “There is every Evidence of good Intentions on all sides but there are too many Symptoms of old Colonial Habits: and too few, of great national Views.”

Volume 20 places John Adams and his family in New York City, and, by the book’s end, in Philadelphia. After a decade in Europe and a few months of semi-retirement in rural Quincy, Adams acculturated to new habits. His trusted circle of regular correspondents changed. For example, in Volume 20, the Adams-Jefferson correspondence recedes. We see more exchanges with Dr. Benjamin Rush, Henry Marchant, John Trumbull, and with the vice president’s son, John Quincy. Busy compiling his Discourses on Davila in the spring of 1790, John Adams renewed old friendships on the page and reflected on his law career. I want to emphasize here that every Adams Papers volume is foundational. We are especially grateful to the editors of the Legal Papers, who have helped us to identify Adams’ allusions, reflections, and rivals at the bar.

Time for a sneak peek! One of the more remarkable letters that we published in Volume 20 is Benjamin Franklin’s last letter, of February 9th, 1790, to his fellow revolutionary and former colleague. For longtime readers of the Adams Papers and fans of American history, this letter is a fascinating bookend to a fractious friendship. Franklin enclosed a 5 February 1790 letter from James Pemberton, a well-known Philadelphia Quaker and antislavery activist, as well as a 3 February 1790 petition from the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. The Society asked Congress for the abolition of slavery and an end to the slave trade. While Adams never replied to Franklin, the vice president did heed the request and laid the petition before the Senate. Despite heated debate, no substantial action was taken by Congress regarding what Adams called “the Quaker petition.”

But John Adams did pause to reflect on the passing of Benjamin Franklin. Just as his Discourses on Davila began to appear in the American press, Adams’s writing took a more fanciful turn. Following Franklin’s death, Adams memorialized the milestone in a playful skit, titled “Dialogues of the Dead.” We do not see a lot of “creative writing” in John Adams’s papers, so this is a unique treat. Adams’s scene stars a cast of characters in conversation [Charlemagne, James Otis, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Frederick II (the Great)] as they await Franklin’s arrival in the afterlife.

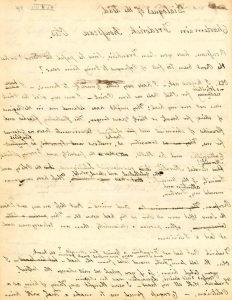

Though it seemed like a quirky choice for the author of serious works like the Defence of the Constitutions, Adams’ sardonic salute showed his Harvard-trained classical roots. In content and style, Adams emulated the Syrian satirist Lucian of Samosata’s Dialogues of the Dead. Adams riffed on Franklin’s science experiments and took a few jabs at his statesmanship. He observed that Franklin “told some very pretty moral Tales from the head—and Some very immoral ones from the heart.” For such a breezy and colorful bit of writing, Adams certainly worked hard to get it right; the manuscript bears plenty of his edits and deletions. We are proud that John Adams’s previously unpublished “Dialogues of the Dead,” along with a previously unpublished draft for a 33rd essay intended for his Discourses on Davila, will both appear in Volume 20.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute. The Florence Gould Foundation and a number of private donors also contribute critical support. All Adams Papers volumes are published by Harvard University Press.

I will look forward to that little essay from John Adams. As noted, his relationship with Adams was “problematic” during their time together in Europe, but both held a mutual abiding respect for the American cause and for the sacrifices made to achieve that success.